Why Measuring Isolated Quadriceps Torque (and Strength) Matters for Return to Running and Sport

When it comes to returning to sport after a knee injury or surgery, one of the biggest mistakes athletes and clinicians make is relying purely on feel.

Feeling strong isn’t the same as being strong — and the quadriceps are a perfect example of that.

The Quadriceps: Your Knee’s Primary Shock Absorber

The quadriceps play a critical role in absorbing load and controlling knee motion — especially during high-demand movements like sprinting, decelerating, and changing direction on the sporting field.

When the quads are weak or inhibited, the body compensates. It might keep you moving, but it’s not true recovery.

A common compensation of a weak quadricep in an athletic setting, is getting a ‘knee valgus’, or knees caving in - yes, that’s right, it’s not always from your glutes!

That’s why objective strength testing matters. It gives you confidence in knowing where your knee is at, and how far away from getting safely back to the sporting field you are.

Why Objective Testing Beats Guesswork

Post-injury, subjective impressions like “it feels strong” or “I can run now” don’t tell us how much force the muscle can truly produce.

That’s where quadriceps torque testing comes in — providing an objective, quantifiable measure of how much force the quads can generate.

How Quadriceps Torque Is Measured

Torque = Lever Arm Length (measured in metres) x Force (Newtons)

Force: measured using a fixed dynamometer (I use the EasyForce system in clinic)

Lever arm: distance from knee joint line to point of force application (shin length)

Result: expressed in Newton-metres (Nm)

Relative torque: divide by body weight → Nm/kg

Quad Index: Torque of the injured leg / Torque of uninjured leg x 100.

Target Torque Values

1.5–2.0 Nm/kg → minimum for safe straight-line running

2.5–3.0 Nm/kg → desirable for return to high-level sport (cutting, landing, sprinting)

Limb Symmetry Index (LSI): aim for ≥ 95 % symmetry between limbs for safe return to high-level sport

If you’re below those numbers, your quads simply aren’t producing enough force to absorb or control the loads required in sport.

Torque measurement for the above client (video).

Force produced (left Quad): 588N

Shin Length: 0.39m (39cm)

Bodyweight: 78kg

Torque (Nm): 0.39 x 588 = 229Nm

Relative Torque (Nm/kg): 229N / 78kg = 2.94Nm/kg.

Based on his results, I would interpret this as;

‘From an isolated quad strength point of view, he has sufficient strength to perform higher level athletic tasks. Let’s move onto more functional testing’.

What if you don’t have access to a dynamometer?

Maybe your clinic doesn’t have one, or you’re someone just suffering from knee pain and are on your own journey of rehabilitation.

It’s not impossible to get some fairly accurate measure of your quad strength!

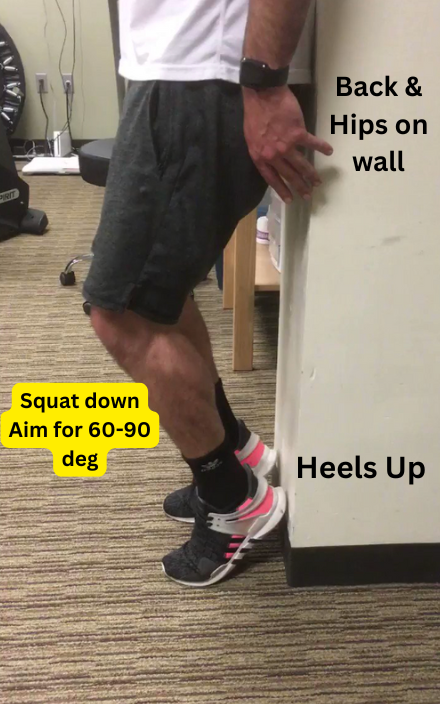

Here’s how I would do it - it’s called a wall squat, but you have your heels on the wall, and toes just on the floor. Your objective is to control your body down, your quads will be the main muscle working.

Start with 2 legs to ‘warm up’ and get the feel of the movement.

Then to test, move onto SINGLE LEG.

Take a video or have someone standing side-on to measure how low you can descend and ascend back up. Compare both sides.

You could assess ‘how many reps’ each leg could do to a certain depth (at least 60 degrees is good), or if you have dumbbells, see how heavy you can go!

Beyond Torque: Why Global Strength Still Matters

Quadriceps torque gives a powerful snapshot of knee-specific capacity — but athletes also need total lower-limb strength to handle full-speed change of direction, sprinting, and deceleration.

This is where we look at compound lifts/movements like the back squat and unilateral strength tests such as the split squat or step-up.

Back Squat Strength: A Practical Benchmark Using 5RM

While quadriceps torque remains my anchor metric for quadricep readiness, the back squat gives insight into overall force production and load absorption throughout the kinetic chain.

Strength Benchmarks for the Back Squat (5RM)

Here’s a simple framework I use to interpret lower-body strength relative to bodyweight.

These numbers aren’t absolutes — they’re guideposts that help match load tolerance to sport demands.

🟢 Return to Straight-Line Running

Men: ~1.2 – 1.6 × bodyweight

Women: ~1.0 – 1.3 × bodyweight

Goal: Enough strength to tolerate early running and deceleration forces safely.

🔵 Sport Readiness

Men: ~1.6 – 2.2 × bodyweight

Women: ~1.3 – 1.8 × bodyweight

Goal: Strength levels commonly seen in athletes with lower injury risk and better sprint, jump, and change-of-direction performance.

🔴 Performance Ceiling / Elite Context

Men: ≥ 2.3 – 2.8 × bodyweight

Women: ≥ 1.8 – 2.3 × bodyweight

Goal: Represents top-end athletic strength — not essential for clearance, but valuable for long-term performance and resilience.

Key point: back-squat strength should complement, not replace, torque and functional testing.

If an athlete meets their torque target but lacks squat strength, I continue to bias knee-dominant strength work until both align.

Single-Leg Strength Testing: The Missing Link

Single-leg performance is often where hidden asymmetries show up — and that’s critical for running and field-based sports.

While the back squat measures global force, unilateral testing highlights limb-to-limb discrepancies and control deficits — both of which are important contributors to a healthy Limb Symmetry Index (LSI).

1. Rear-Foot-Elevated Split Squat (RFESS) 5RM

Reliable method to test unilateral leg strength and symmetry (ICC ≈ 0.73 in strength research)

Excellent bridge between rehab and sport — challenges hip, knee, and ankle stability

Aim for < 5 % asymmetry between sides (or an LSI ≥ 95 %) and progressively load to ~0.75× bodyweight held as external load

2. Loaded Step-Up Test

Functional, sport-transfer drill reflecting real-world unilateral loading

Being able to perform 5 step-ups (to parallel thigh height) with ~0.6–0.8× bodyweight load signals strong lower-limb capacity

Step height should match your sport demands — e.g., 12–16″ box for runners or field athletes

These can be used interchangeably depending on phase and equipment.

I often begin with split-squat assessments early, then progress to step-ups as we restore force acceptance, symmetry, and coordination.

How I Use These Measures Together

In clinic, readiness is never based on one test alone. Instead, I combine objective torque, compound strength, and unilateral control to form a complete picture of an athlete’s strength and capacity profile.

For example, when seeking readiness to begin running in an athlete recovering from an ACL repair, here’s a few criteria I typically want to see ticked.

✅ Quadriceps Torque >1.5Nm/kg

✅ Back Squat >1.2x Bodyweight

✅ Do a split squat full range of motion + 25% BW

Note: Clearance for competitive or high-level sport should also include qualitative assessments — such as running gait analysis, agility and change-of-direction testing, sprint or top-speed assessments, and sport-specific movement drills.

Together, these layers ensure not only that the athlete is strong enough, but that they can also move efficiently, confidently, and reactively under the demands of competition.

The Takeaway

Return-to-sport decisions are too important to rely on guesswork.

Objective isolated testing of the quadriceps — measuring true torque output — should always be complemented by functional strength tests like the back squat or single-leg squat (ideally with force-plate data if available) and running assessments that evaluate how that strength translates into movement.

Together, these layers — including a Limb Symmetry Index of 95 % or greater — provide the most complete and reliable picture of whether an athlete is genuinely ready to return — not just symptom-free, but physically capable of absorbing and producing the loads their sport demands.

Conclusion

Whether you’re a physio, coach, or athlete, I hope this gives you a clearer framework for measuring strength and capacity objectively.

If you’re curious about how to apply this testing in clinical practice, or you’d like ideas for alternative ways to assess quadriceps strength without access to a dynamometer, I’d love to help.

You can reach out with questions or case discussions — I’m always happy to share insights and practical ways to integrate these methods into everyday rehab and performance work.

Not Ready for Testing Yet? Start with Strong Knees

If you’re not yet ready for formal strength testing but want to start rebuilding your knee safely, check out the Strong Knees System – Foundations Level 1: a structured online program designed to restore confidence, rebuild quadriceps strength, and improve movement control.

👉 Learn more about the Strong Knees System here

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ryan Tan is a London-based Spinal and Sports Physiotherapist with over a decade of experience helping clients recover from complex injuries and return to the activities — and sports — they love.

He holds a Certificate of Spinal Manual Therapy (COSMT), an advanced qualification in spinal care, and is also trained in Osteopathic Spinal Manipulations (OMT).

Before relocating to London, Ryan was the Clinical Director of a leading physiotherapy clinic in Hong Kong, where he built a reputation for solving persistent spinal and sports-related injuries.

He now works closely with national-level sports doctors and knee specialists, providing evidence-based physiotherapy and advanced rehabilitation for high-performance and competitive athletes returning to sport.

Now consulting through Ultra Sports Clinic at Third Space gyms (Tower Bridge and Canary Wharf), Ryan combines expert manual therapy, dry needling, and gym-based rehabilitation to deliver long-term solutions — not quick fixes.

If you’re struggling with an injury that’s been holding you back, Ryan offers personalised, one-on-one care to help you move better, feel better, and perform stronger.